Insights | Articles

Leading when change is unwelcome.

What do you remember most about the Great Recession? For me, the first thing that comes to mind is painting. It’s impossible to worry and paint at the same time, and that’s what got me through the financial crisis.

That crisis brought huge changes along with it, and some were horrible. In other ways, it provided a reset. In my case, painting became essential, so much so that I eventually rented a studio I shared with six friends. It’s continued to be my haven from all manner of storms, including the recent ones facing the nonprofit community I serve.

Yet even havens aren’t immune from storms. Our studio building was sold, and the new lease terms were so egregious that we had to move. Change is relentless. And we generally fight and struggle against it. My group was no exception.

I understand that the travails of seven artists are trivial compared to the existential threats facing many organizations. But the less dire circumstances allow us an easier look at how we face change, and how we might better cope with it. Here are three stops on a journey that was far more painful than it should have been.

The moment we decide.

It was New Year’s Day, 2006. I knew that I wanted to make the move from renter to homeowner, but I wasn’t quite ready. Still, I put the top down, whistled for the dog to hop in the car and drove off to explore different parts of town. I was just going to get a feel for pricing.

I spent the afternoon driving through one neighborhood after another looking at houses. It’s funny what goes through your mind during an exercise like this. Too big. Too ugly. Needs too much work. Who would choose that paint color? There was nothing to get excited about. Good.

Hours later, just as it was time to head home, I came to a four-way stop and spotted a discreet “for sale by owner” sign. Pulling in front of the house, I said aloud: “Well, this is it.”

Enter panicked inner monologue: “What am I thinking?” “I have absolutely no business buying anything that costs this much.” “Starting today, I will only eat ramen.”

Anxiety accompanies decisions; it also delays them. For many, 2025 was (understandably) a year of hesitation. So, let’s do something different. Let’s begin 2026 by considering what prompts decision-making, because progress demands it.

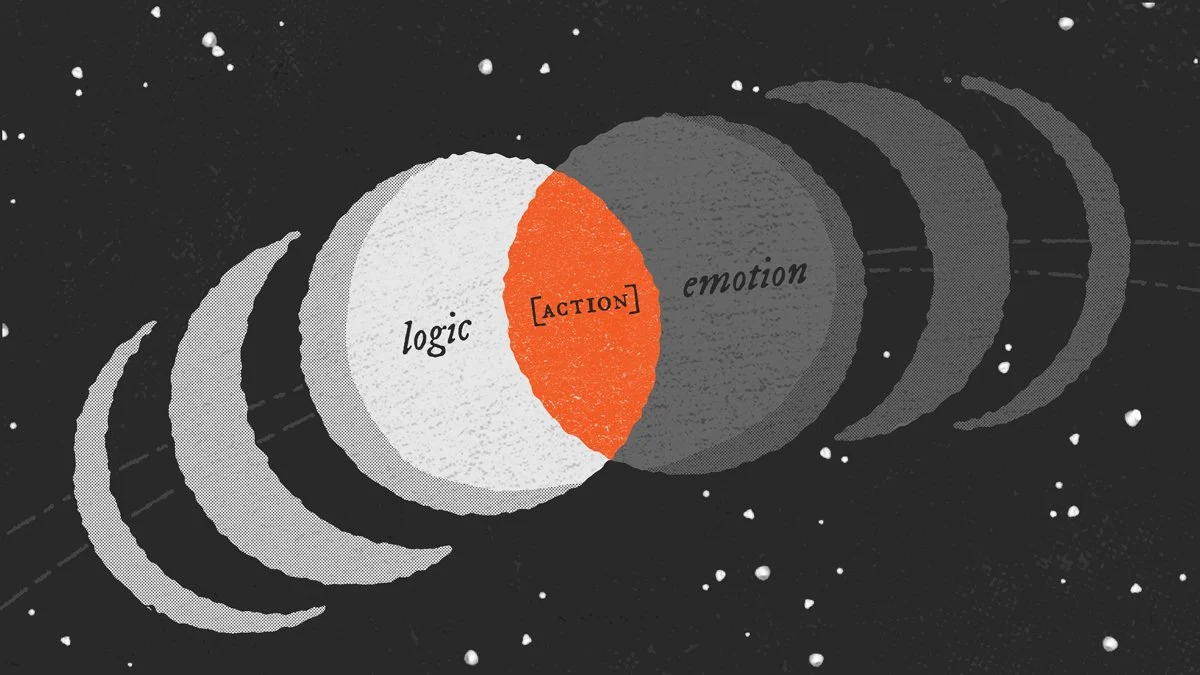

Behavioral science tells us that big decisions rarely hinge on logic alone. In fact, the larger the decision, the more likely it is that subconscious forces are doing the heavy lifting. Here are four principles that often determine when deliberation gives way to action.

What donors remember.

I was almost to Union Square when it suddenly got quiet. It had only been two years since 9/11, so my thoughts turned to terrorism. Then came the radios. Taxis turned theirs up and opened their windows and doors so pedestrians could lean in and listen. It was New York City’s 2003 blackout, and all I wanted was to get back to my apartment where things felt safe.

All these years later, my memories of that afternoon remain vivid. Psychologists call these flashbulb memories, moments where we remember not only what happened, but also how we felt. They stick because of context. Who we were with. The weather. The conversation.

Most of us won’t remember 2025 fondly, at least as it pertains to our work. I’ve watched countless fundraising campaigns launch this year. Meanwhile, there has been record turnover among development officers. As such, the need to nurture donor relationships has never been greater, making memorable interactions essential. If your fundraising efforts are feeling like hindsight in the making, here are a few things to keep in mind as you look ahead to next year.

When truth gets twisted: three ways to combat misinformation.

My job is to study people, specifically what motivates the decisions they make. I started when I was about seven years old in the TV room. Shows like Three’s Company, I Love Lucy, and The Odd Couple were built entirely on misunderstandings. Someone overheard half a conversation, misread a situation, or jumped to a conclusion. A single wrong assumption would spiral into a comedy of errors. Most importantly, the audience always knew the truth, which made watching the confusion unfold even funnier. Back then, misunderstandings made for great television.

Today, misinformation is a different story. Behavioral science helps explain why misinformation spreads so easily and why it’s so hard to correct. For nonprofits and foundations, this dynamic poses a real challenge: how to communicate truth in a way that cuts through noise, earns trust, and doesn’t get lost in the scroll. So here are three ways to respond.

The Courage to Fix Things: Ways to Refocus for Greater Impact

I was reminiscing with a coworker about a younger version of our firm (and me) and recalling some big risks. Thankfully, most paid off well, and I’m grateful for those outcomes. My next thought was, why with so much less experience, was I so confident? How could I have been so bold, and where did that gumption go?

I’ve come to realize that early in our careers, we sometimes succeed because we don’t know better. Next comes a certain timidity that stems from having gotten a taste of failure. Eventually, you move past timidity to the real work – fixing things. For those in this stage of their careers, or those ready to begin it, I thought it might be helpful to share the most common mistakes I see and how to fix them.

From history class to today’s headlines: five ways to defend against division.

Majoring in history was one of the best decisions I ever made. I love the objectivity and detached analysis of the causes of major events, and how those events contribute to a much larger unfolding of consequences. I’ve always found comfort in knowing that whatever today’s troubles may be, we’ve been through something similar many times before.

But not everyone shares that comfort. When the pace of change feels relentless and the noise around us becomes deafening, perspective is the first thing to go.

That’s because our minds are wired to instill belonging, manage uncertainty, and make sense of complexity. There’s real science behind why we’ve drifted so far apart, and nonprofits can benefit from understanding it. Here are five leverage points to keep in mind.

Blue skies and bubble wrap.

I don’t think well sitting still. And many years ago, there was a gallery around the corner from my office. Whenever I got stuck, that’s where I’d go to pace and ponder.

For months, I was especially enamored with one of the paintings. What the gallery owner called a “statement piece,” it was all blue sky and cumulus clouds, six feet long by two feet high. I was 29 years old when I bought it as a celebratory gesture after being named a VP. October had just begun when I took it uptown to be framed.

Cut to a call in February asking when I wanted my newly framed piece delivered. In between, the dot-com bubble had burst, taking my job with it. Now all I saw within the frame was fear, dollar signs, and regret. Taking the subway downtown in the cold, lugging a six-foot canvas covered in bubble wrap, is something I’ll never forget. So, there’s a little déjà vu when I think about today’s climate for many nonprofits.

Things looked so good, then so grim. It feels awful because we have a systematic bias toward assuming continuity rather than volatility. But nothing is ever as good or bad as it seems. Here are five steps to help your team deliberate and see its way through the clouds.

Leading through whiplash: finding stability in change.

My dog Hazel knows what I’m going to do before I do it. Reaching for my running shoes prompts spin-arounds, and my keys cue a rush to the door. Her behavior reminds me that I have rituals and calcified routines I don’t even realize. Similarly, there are behavioral anchors within our organizations. We’ve nurtured and cultivated programs for years and found conviction in their outcomes.

That makes the recent chaos in our sector feel more upending than simply unsettling. The pace of change, intentional by the current administration, hasn’t allowed leaders time to plan or develop contingency strategies.

Change isn’t a choice, but resistance to it is deeply rooted in how our brains are wired. A better understanding of this can reveal how this avoidance may not be serving ourselves or our organizations. So here are the biggest reasons we resist and four steps for achieving the opposite.

Cracking the code of mental money quirks for more successful fundraising.

We all have differing financial priorities, but what fascinates me is the behavioral economics concept that drives them, mental accounting. Logically, we know a dollar is a dollar, but we don’t behave that way. Mental accounting is about how people irrationally code, categorize, and evaluate money, leading them to make biased and sometimes irrational decisions. Implemented properly, nonprofits can benefit a great deal from this concept, particularly when it comes to leveraging five tendencies in fundraising.

Shape your narrative, or be shaped by its gaps.

Mrs. Baughman said we were going to elect a classroom president. Someone nominated me. I guess the point was to teach us fourth graders how democracy worked. The ballot was secret, but voting for myself felt boastful. Of course I lost the election — by one vote.

I think many cause leaders similarly undersell themselves. Sometimes modesty is the culprit. Other times it’s because they haven’t prioritized communications.

But as we’ve seen a lot lately, if you don’t control your narrative, someone else will.

I know the reasons communications isn’t a priority. I also know the most frequent mistakes nonprofits and foundations make. So here’s four angles on how we can improve, plus a process that reveals an easier way to do so.