Is it time to aim differently?

We’re more technologically evolved and connected than ever. Smartphones allow endless options for shopping, dining and entertainment. Societies are more environmentally aware, diverse and inclusive. We can work, learn and bank from home, and our work schedules are more flexible than ever.

Yet running a foundation or nonprofit has never been more challenging. One can easily ruminate about the causes for division, the competition for donors/grants/staff, or the lack of trust that seems so pervasive. And while commiseration is tempting, the mavericks I admire and collaborate with aren’t distracted by these truths. Instead, they put their heads down and build.

Rather than continuing to aim for an increasingly elusive bullseye, they push one ring further out on the dartboard, finding the next adjacent group to join their movement. They grow communities through inclusive dialogue.

This move is right out of the Stanford Social Innovation Review’s collaboration with our friends at The Communications Network on a new series of articles, “Communication in a New Era of Social Change.” I love their take on, well, just about everything, so let me offer an example of how my team implemented such a strategy.

We were working on an effort to recruit foster families. In search of insights and inspiration, our client arranged a series of interviews for us with current foster parents. The conversations were indeed inspiring.

Among them were single mothers who worked full-time and cared for multiple children, as well as families that welcomed multiple siblings into their homes.

Some grew up in families who fostered or had seen neighbors and family friends step in to care for children in need. One mother told us: “Even as a young girl, I knew I wanted to have foster children when I was older.” The accounts were humbling. I soon began referring to our respondents as Olympic Parents.

But instead of informing our dialogue with prospective foster parents, the interviews were making our task more daunting. There are only so many of these rarified super-humanitarians. We needed to widen the circle, we needed to find an adjacent audience.

The parents we interviewed were certain. Circumstances had given them a purpose and turned them into the ideal specimens. So what if we took one step away from folks who already had a calling to approach those who were searching for one? Imagine giving them a glimpse of the fulfillment we heard from the Olympians. That thought led us to the moniker for a new audience, Foster Curious.

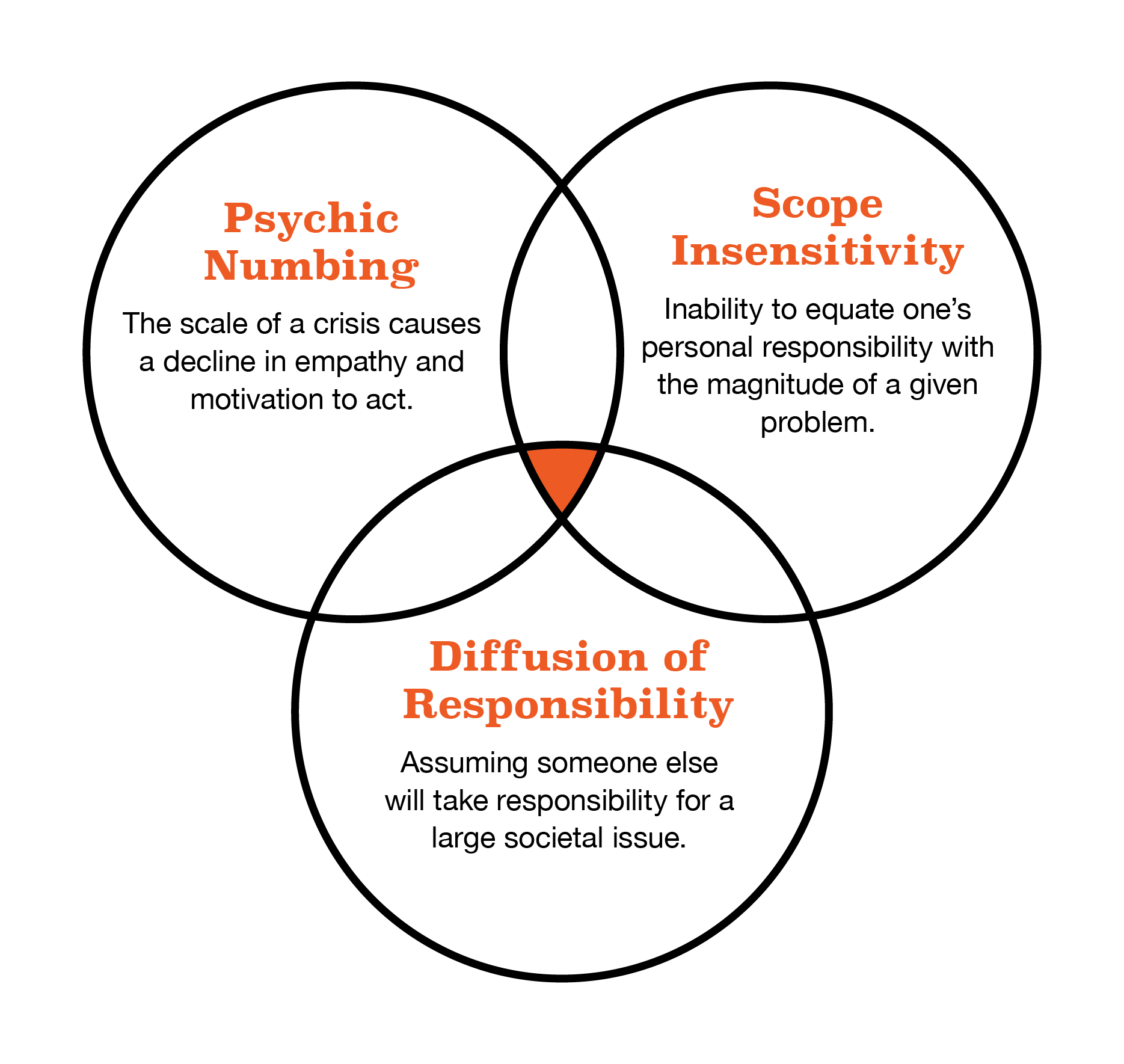

For this group, leading with stats about the thousands of children who needed foster homes would only make the problem seem insurmountable, possibly so much so that our message would be ignored. The biases and heuristics behind this conundrum look like this.

To become foster-curious, folks didn’t need to see an endless parade of forlorn children, they needed to see how life had serendipitously interceded for others like them. They also needed to know that a prospective foster parent didn’t have to be a superhero, just someone who listened to that little voice in their head. Someone willing to entertain the idea of what fostering might be like. That’s a mental dance evident here:

All of this is about widening communities. Creating invitations. Exchanging division for belonging.

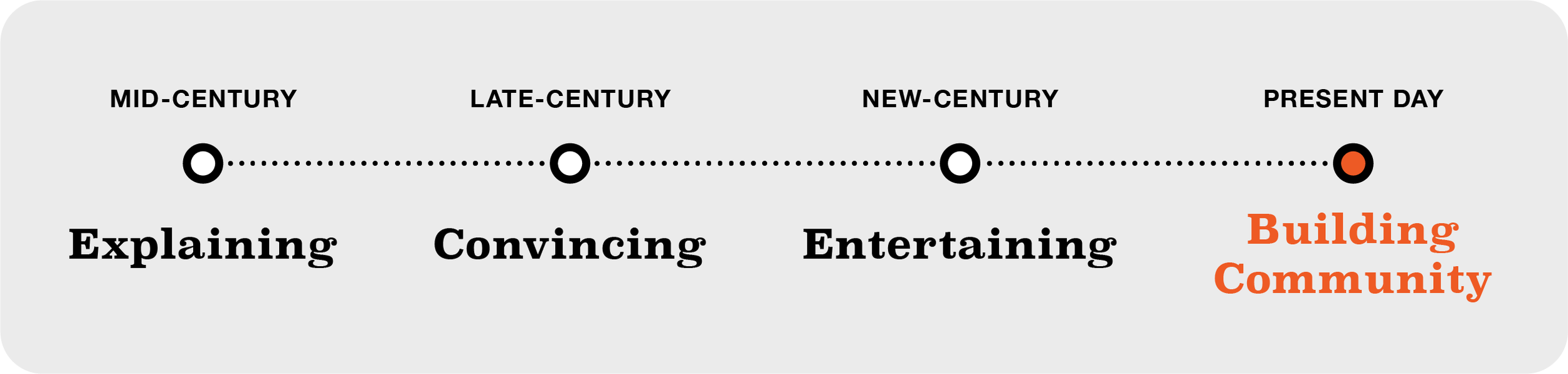

It’s the extreme opposite of an old debate about eliminating hostile marketing terminology born in the 1950s from World War II battle jargon. There are target audiences and campaigns. I’ve long thought these labels mattered little. That the sanitizing of communications terms doesn’t make us more empathic or effective.

I’m starting to see things differently now. On the continuum of marketing strategy, I see a new addition. One positive reality emerging from the distrust and division of our post-COVID world is coming into focus. Here’s how I see it.

This is great news for cause marketers. It’s time to get optimistic my friends, and above all, to build. Our specialty is on trend. Let’s make the most of it.

Yours in good,

Kevin